Conventional spring break plans typically involve time away from campus for just that, a break. But this past spring, a group of students — not all of whom are pursuing a science-related degree — voluntarily spent the week in Virginia Western’s Biotechnology Lab for an innovative, one-week course in cell culturing, BIO 195: Industrial Biotechnology.

“We’re the foundation, so beyond, they go out here and find out, ‘Hey this skill, I might be interested in it.’ It’s a perfect training ground,” said Dr. Heather Lindberg, associate professor of biology and Biotechnology Program head. The course teaches basic aseptic techniques and the processes required for culturing eukaryotic cells safely.

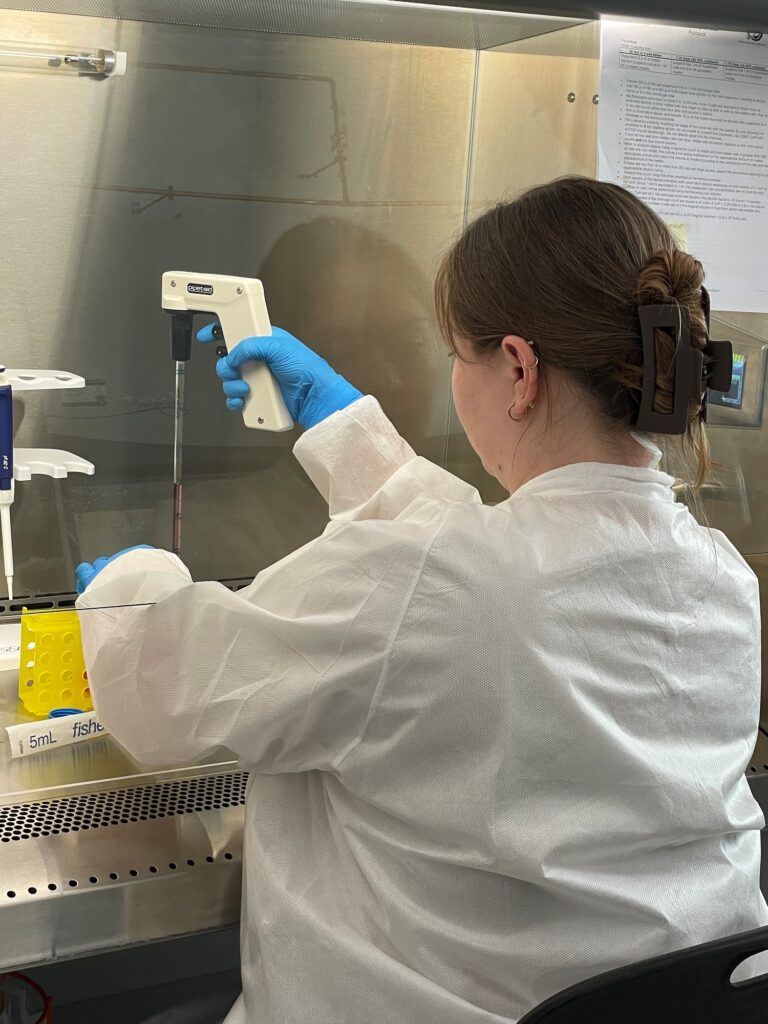

“It’s 15 hours, it’s over spring break. This is unlike a lot of the classes they take. It is 100 percent skills-based,” Lindberg said. “I give them enough theory to understand why we’re in the containment hoods, why we’re doing all of these things, but it’s about hands-on, about them doing it. I want them figuring out what these cells look like, or even if they like doing this work.”

The course enrolled a dozen students, including two faculty members. Some of the students know they will be using these skills in the future. “It’s good for career development,” said Ezekiel Luebeck. “I plan on getting into regenerative medicine, so a lot of what we’re doing here is what I’ll be doing as the main part of my work, just trying to get cells to grow and to culture them.”

Not every student will go on for further biotechnology study, but the techniques learned in the course can easily be used in other contexts, such as plant propagation.

“I’m actually not in any science majors, but I do find it interesting, the hands-on stuff, so I just wanted to try it out,” said Sydney Spruill.

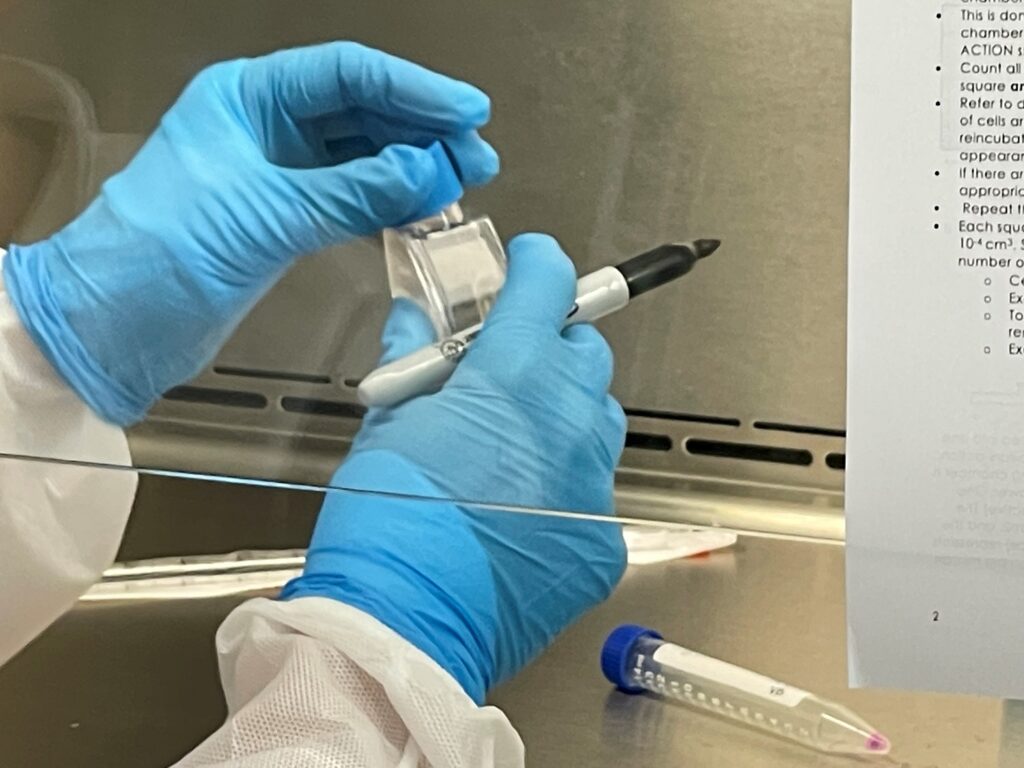

Partway through the week, students worked out mathematical formulas, then took their samples to Biotechnology Lab’s clean room. “I put a marker in your hood, because you are going to have your own flask, and you need to make sure this is labeled well enough so you know what yours looks like on Friday,” Lindberg told the students.

She added practical tips. “With your flasks, do not try to label them right away. You get ethanol on that Sharpie, it will not write. Let it sit for a minute,” she advised them as they sat at containment hoods.

Lindberg continued to walk the students through the process. “Before you add your cells, you need to carefully remix your cells. They’re heavy, they will have fallen to the bottom of your tube. So if you don’t remix your cells to get them in suspension, all the careful math that you just did is null and void.”

The students worked with HeLa cells, the story of which was made known more widely through the 2010 book, “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Lacks was born in Roanoke in 1920, and the city has recently honored her legacy with a statue. Lacks died of ovarian cancer in Baltimore, where researchers harvested her cells without her knowledge. Her cells’ extraordinary ability to regenerate has contributed to decades of medical research and discovery.

“HeLa cells are very, very tolerant, so they are a perfect training tool for students to where they don’t have to be perfect,” Lindberg said. “They can focus on the technique they’re using, and to prevent contamination, but if they don’t seed their flask exactly right, if they don’t do things exactly as necessary, they can still move forward.”

The use of HeLa cells had particular meaning for student Laine Wegener, who had taken a previous class with Lindberg. “It was really interesting learning that we’re growing ovarian cancer cells, because I plan on being an OB/GYN when I’m older,” Wegener said, “so it kind of goes hand in hand with what I’m interested in.”

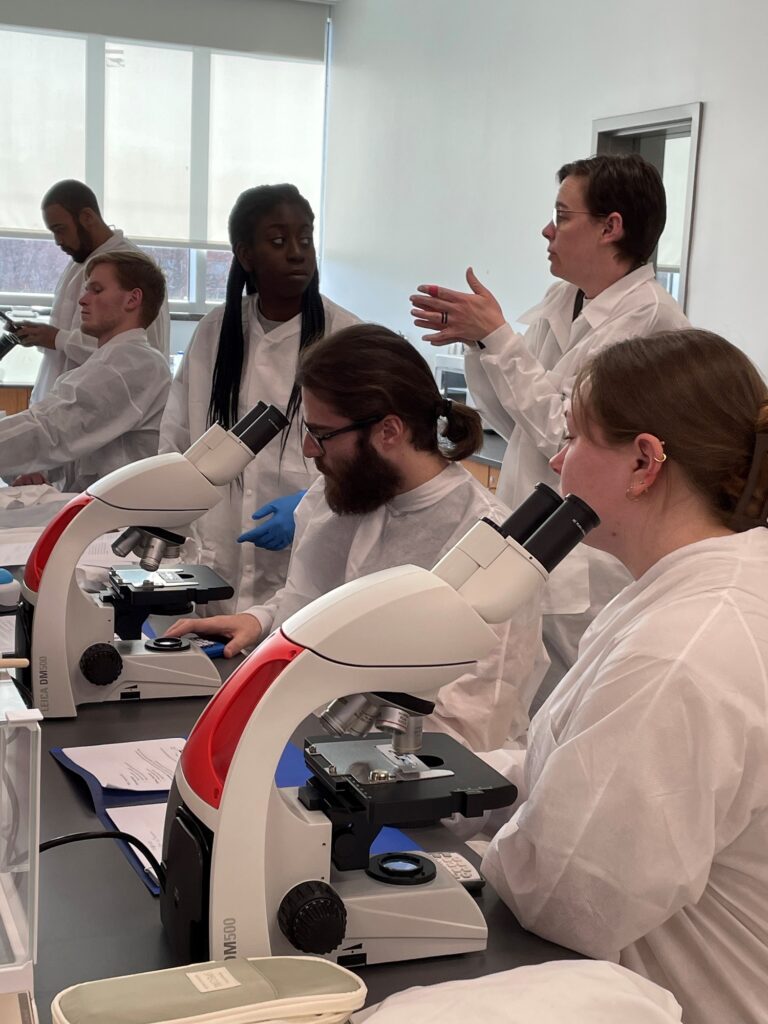

The class met in the lab in three sessions, with cells growing throughout the course of the week. “It opens a different world, when I’m showing students the difference between what these cells look like in the flask versus what they’re looking like underneath their microscope,” Lindberg said. “It’s the same cells, so they can kind of see how malleable these cells can be under different conditions. And they learn that biotechnology doesn’t have to be scary — it can be a lot of fun.”

Learning cell culture techniques at this stage of their studies has an array of benefits, Lindberg said. “For students who are moving on, potentially into research, this is valuable, to where they can walk in to a PI [principal investigator’s] office at their four-year and say, ‘I learned how to do this. I like it,’ which is a valuable training tool. Same for industry, where these students have tested it once or twice. If they don’t like it, then, it’s like ‘I won’t look for a job that has that as their main piece.’ Which is a value, too, to the student and also the industry, because then they’re not hiring someone who looks like a perfect fit, but then they get in there for two weeks and go, ‘Oh, this is all cell culture, I don’t want to do this.'”

Some students knew that’s exactly what they want to do, such as Kiana Watt. “I’m in the Health Science Program, so when I saw Cell Culturing, I was like, ‘Cell culturing!’ And I was probably a little bit too into Grey’s Anatomy and all the cool stuff they do with cell culturing,” Watt said. “Now that I’m in the class, I really see how it could apply to my major, because I’m going into neuropsychology, and there’s a lot that is not understood on the inside of the brain.”

This class is part of the larger regional Roanoke Biotechnology Project, with funds provided by the City of Roanoke and the Virginia Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD). “We are thrilled to bring this type of real-world experience to our students and our College community,” said Amy White, Dean of STEM and Workforce Solutions at Virginia Western. “We are also so happy to be part of this collaborative and forward-thinking ecosystem, which includes partners such as the City of Roanoke, VERGE, the VT Corporate Research Centerer, Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and Carilion. The impact on our students is meaningful and may affect their long-term trajectory.”

Watt, for one, is part of that impact, as she would like to see more understanding of the “cellular matrix” in the brain. “Maybe one day, I can be cool enough to culture a brain.”